A student in India takes part in an online course while schools are closed due to the coronavirus

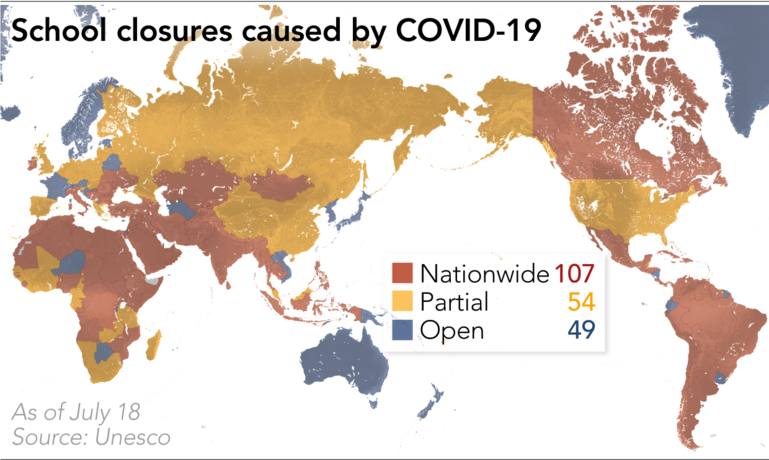

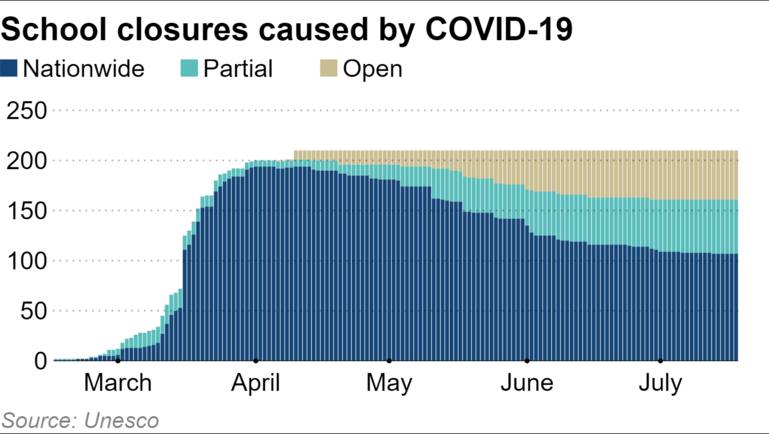

Schools in more than 100 countries and regions remain completely closed because of the coronavirus pandemic, widening the education gap between advanced economies and middle- and low-income nations unable to provide online learning. In June, most of the schools in Uruguay reopened, as they did in Japan, with children in Australia and Vietnam also getting back to the physical classroom.

However, these countries represent the minority. According to UNESCO, only 49, or 23%, of 210 countries or regions were able to completely reopen pre-elementary to high school education as of July 18. Fifty-four countries and regions, including the U.S., U.K., Germany and China, have partially reopened schools.

But in 51% of countries and regions, schools are still completely closed. Roughly 1.07 billion children live in these areas, accounting for more than 60% of the children in the world.

Lingering school closures are particularly common in Asian, African and South American developing countries. When the countries and regions are categorized by income levels, about 90% of low- and lower-middle income locations are still not able to reopen schools nationwide, due to COVID-19.

The closure of schools affects education in a negative way. A study by researchers from institutions such as Brown University estimates that for the academic year starting this fall, U.S. elementary school students will only achieve 37% to 50% of the math proficiency that they should have.

According to research carried out by professor Harris Cooper at Duke University and others, children from low-income families experienced a reduction in math test scores over summer vacation, even before the pandemic. School closures have continued for more than four months in some countries — far longer than summer breaks — and this long absence will certainly have a negative effect on education levels.

The World Bank estimates that absent effective policy from governments, school closures lasting five months will lower the lifetime earnings of these children by a total of $10 trillion. School closures have also highlighted the issue of inequality, especially in emerging economies.

In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte in May laid out his priorities in keeping the country safe. “For me, vaccine first. If the vaccine is already there, then it’s OK,” he said, insisting that until there is a vaccine available, schools cannot be reopened.

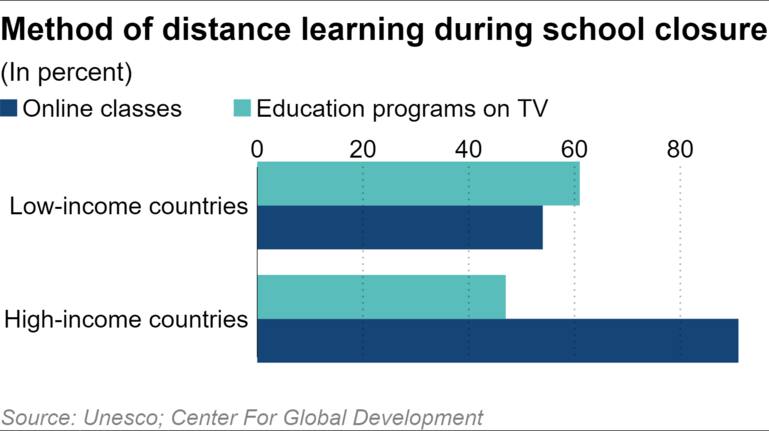

However, if school closures continue, according to nongovernmental organization Save the Children, 10 million children in the developing world will not be able to go back to school. This will have significant effects on such issues as child labor and child marriage, because, as the pandemic and related economic fallout continue, there will be more incentive to work and earn rather than to learn. Another area where inequality has been shown up starkly is online education.

Nikkei compared UNESCO data on where schools have reopened with a study on online education opportunities by the Center for Global Development, a U.S. think tank. The analysis shows that 91% of high-income countries had some sort of online classes taking place as an alternative to in-school learning. In low-income countries, this was a mere 54%.

Some countries are taking new steps to avoid further losses of learning opportunities. The U.K. is using graduates as tutors to enhance children’s education in low-income areas. The assistants are paid 19,000 pounds ($24,000) a year, which helps cover living expenses.

Developing countries are also striving to find new ways to deal with the crisis. In Bangladesh, teachers are producing education programs that are broadcast on state television. Mozambique, meanwhile, is making use of the radio to reach children. However, these methods are not interactive; students cannot raise their hands to ask questions. To address this particular issue, India is trying to prevent students from falling behind by using education apps via smartphones.

In Japan, schools have reopened, but according to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, interactive online courses were only conducted in 8% of elementary schools and about 10% of middle schools.

Inequality in education influences the competitiveness of the country decades later. While countries are striving to strike the balance of preventing new infections and reopening the economy, education for the future must also be considered.