SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son, who once aspired to be a schoolteacher, is now throwing his support behind young “representatives of humans.”

As Vision Fund bets on tech, he’s gambling his own money on humanity

Masayoshi Son seemed to be joking, but it was difficult to be sure. “Our fund will invest at least 10 billion yen, or an average of 100 billion yen,” the SoftBank Group founder and CEO said at a networking event for young entrepreneurs and gifted students, held in Tokyo the day after Christmas.

“We have money,” he cracked. The 61-year-old is famous for making bold — some say reckless — bets through SoftBank and his Saudi-backed Vision Fund. But even if Son was just teasing the crowd about average investments to the tune of $900 million, it was all part of his larger message: I’m here to help you achieve greatness.

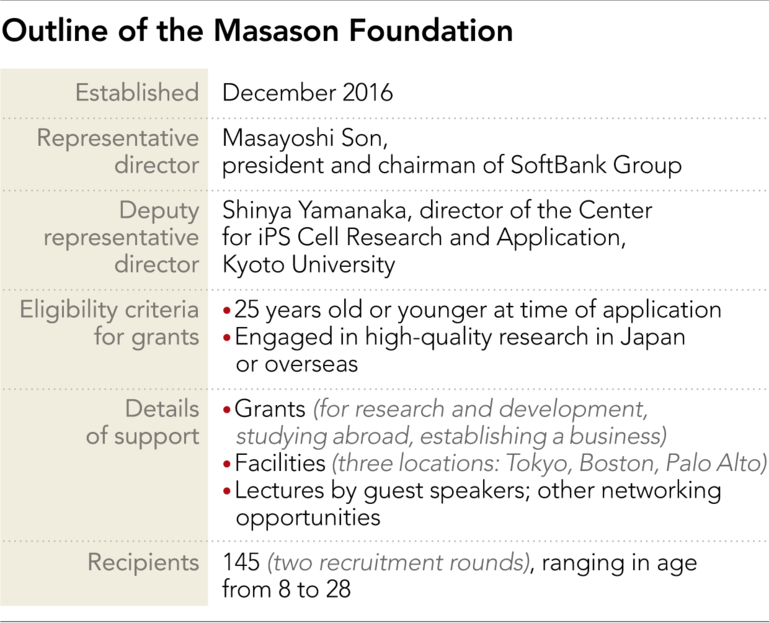

Listening to his speech that day were over 100 beneficiaries of the Masason Foundation. Son, who once aspired to be a schoolteacher, established the organization with his own money in late 2016 with the express purpose of fostering young people with unique talents.

For investors, the foundation may be worth watching to see what intriguing startups Son digs up.

For everyone else, it could have implications too. Son has spoken of how developing human abilities might save us from submitting to artificially intelligent robot masters.

The Masason Foundation provides not only funding but also networking opportunities.

The website says the foundation is for those who will “create the future.” Members get access not only to financial grants but also networking opportunities and an exclusive club-like facility in Tokyo called Infinity, which features drones, virtual reality headsets and, of course, SoftBank’s well-known robot Pepper.

Applicants must meet two basic criteria: they should be no older than 25 when they register, and they have to show “exceptional talent.” So far, 145 have made the grade. The youngest is 8-year-old Yuki Haruyama, who showed interest in the immune system and microorganisms as a toddler and wants to research “prehistoric life that possessed some characteristics humans no longer have.”

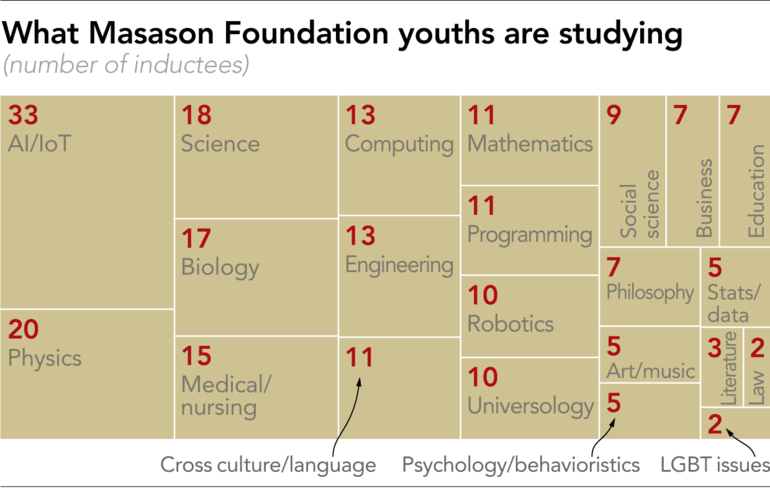

Some members have already created businesses based on original technologies and ideas, but most are simply “gifted” — they have excelled in national or international contests in mathematics, physics, robotics, artificial intelligence and other fields.

The website says the foundation is for those who will “create the future.” Members get access not only to financial grants but also networking opportunities and an exclusive club-like facility in Tokyo called Infinity, which features drones, virtual reality headsets and, of course, SoftBank’s well-known robot Pepper.

Applicants must meet two basic criteria: they should be no older than 25 when they register, and they have to show “exceptional talent.” So far, 145 have made the grade. The youngest is 8-year-old Yuki Haruyama, who showed interest in the immune system and microorganisms as a toddler and wants to research “prehistoric life that possessed some characteristics humans no longer have.”

Some members have already created businesses based on original technologies and ideas, but most are simply “gifted” — they have excelled in national or international contests in mathematics, physics, robotics, artificial intelligence and other fields.

The Masason Foundation “is unprecedented in Japan, and the world hasn’t really heard about it yet,” said Yasuyuki Genda, senior director of the program as well as personnel administration at SoftBank.

Hirotaka Nishimura founded Metrica, aiming to provide AI-driven health care tools.

Genda said the foundation wants its members to “do what they want to do.”

“We have not set goals, such as how many entrepreneurs we should nurture,” he said. “However, whether it’s through entrepreneurship or academic pursuits, it is very important for the foundation to return some kind of achievements to society.”

One member who appears well on his way is 24-year-old Hirotaka Nishimura. The medical student founded a company called Metrica last April, aiming to provide AI-driven health care tools. His core product is an application that removes the language barrier when Japanese hospitals and nursing homes hire foreign workers to cope with the country’s labor shortage.

Metrica says its app translates medical jargon between Japanese and several other languages, while learning on its own to continually improve accuracy. The company quickly racked up sales in the tens of millions of yen, thanks to orders from clients including a major medical equipment maker.

Nishimura, who was at the Dec. 26 event, took Son’s remarks as motivation. “I figured I’d sell my company when its corporate value reached billions of yen,” he said. “But such a lax stance is not allowed.”

One thing that makes the foundation unique is its bespoke approach. While conventional programs for entrepreneurs or students set limits on financial assistance, Masason offers “made-to-order support.” Members can request funding for anything from conducting research to studying abroad to launching a business. If a member needs a high-performance computer, the foundation will supply the cash.

When he set up the foundation, Son said he would offer “unlimited” money for members to study abroad or buy tools for research. “You don’t need to pay back at all, even 1 yen,” he said. “I just want to support you.”

Kensho Tambara set up a company, Amatorium, to distribute the work of young artists.

The foundation has not disclosed the actual value of its grants, but it is believed to have supplied hundreds of millions of yen. “The real value of the foundation comes from connections with people, not money,” said Kensho Tambara, 26, another member. Tambara is a typical example of the atypical types the Masason Foundation attracts. He quit an elite Japanese high school because he “didn’t like to study.” He enrolled at Harvard University to pursue child education and psychology, but after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami hit northeastern Japan, he took a leave of absence and returned home to set up a nonprofit organization.

When he went back to Harvard, he changed his major to art history, and later took more time off to immerse himself in Tokyo’s art scene. After graduating, he decided to set up a company to distribute the work of young artists. He was mulling how to go about this when he found Masason.

With money from the foundation and help from fellow members, he created Amatorium. The company is preparing to distribute scanned artwork for high-definition displays by the end of this year. The service will use blockchain technology — the system that underpins cryptocurrencies like bitcoin — to protect the artists’ data.

Kensei Demura’s company, D.K.T., is working on a robot that helps with household chores.

Tambara pops into Infinity whenever he can. “It makes me happy to chat with brilliant people from the same generation,” he said.

The networking has been crucial for Kensei Demura, a 21-year-old member running a robotics startup. His company, D.K.T., is working on a robot that helps with household chores and is capable of communicating, aiming for a 2020 release. It was designed by another Masason member.

This sort of collaboration is exactly what Son had in mind. In his speech at the event in December, he spoke of how interactions between gifted individuals can lead to innovation. “People with unusual talents evolve when they inspire one another,” he said.

In this sense, the foundation is similar to the Vision Fund and SoftBank, though it is a distinct entity and SoftBank has a policy of not recruiting from the membership.

As a CEO, Son has made no secret of his strategy to build an “ecosystem” of companies that, together, will produce the next big things in technology. Likewise, he expects foundation members to pool their knowledge and capabilities to innovate for the greater good. “A new ecosystem that changes common sense will be created,” he said.

Of course, even young geniuses need sage advice now and then. The foundation has put together an all-star cast of directors and counselors, including Shinya Yamanaka, the Nobel Prize-winning stem cell researcher; Bernhard Hodler, CEO of Swiss private bank Julius Baer; the heads of top Japanese commercial banks; and even a master of shogi, or Japanese chess.

Yasuhiro Sato, the chairman of megabank Mizuho Financial Group as well as a foundation director, has told 21-year-old member Nana Matsuoka to contact him “anytime” she needs help with her venture, which seeks to address the growing problem of childhood obesity in Vietnam.

In the country’s urban areas, 16% of children are classified as overweight — more than double the world average. Matsuoka, one of the foundation’s first members, started a company that offers kindergarten teachers and parents of young children nutrition guidance in the form of card games. It also runs farms that allow city children the chance to experience nature.

She plans to start a new online service providing dietary advice by the end of the year, and eventually wants to expand into neighboring countries such as Thailand.

Like Tambara, Demura and Matsuoka, most of the foundation’s members are Japanese. But half of the 145 are engaged in some sort of activities overseas, and Son aims to make the membership more international. “I want to have a 50-50 ratio of Japanese and foreign members within five years,” he said in December.

The foundation has set up Infinity-like facilities in Boston and Palo Alto, and it intends to open more worldwide. The SoftBank chief is also exploring cooperation with schools for gifted students in the U.S. and Singapore.

However, the foundation’s somewhat scattershot approach — backing anyone from 8-year-old prodigies to robot developers and artist — will do little to dispel criticism that Son is not so much a visionary but rather an impulsive daredevil who throws money around and makes questionable alliances.

Through SoftBank and the Vision Fund, Son has invested in a dazzling array of companies, including ride-hailers Uber Technologies of the U.S., Didi Chuxing of China and Grab of Singapore as well as British chip designer Arm Holdings, Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba Group Holding and American shared office startup WeWork. Money has also been pumped into smaller AI and robotics startups. Son recently told CNBC that the Vision Fund has already invested around $70 billion.

But his decision to team up with the Saudis on the Vision Fund hurt SoftBank’s stock last year, as allegations swirled that Riyadh was behind the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the kingdom’s consulate in Istanbul. At one point, SoftBank shares were down 40%, though the stock has recovered and the company’s market value exceeded 11 trillion yen at the end of February — up ninefold in a decade. Son himself, soon after he launched the foundation, admitted he was unsure what it would achieve. “I don’t know specifically how this foundation can contribute to humans in the future.”

But he has framed the project as a potential answer to a frightening prospect: the “singularity,” or the moment AI becomes smarter than the human brain.

With his investments in AI, robots, and the “internet of things,” Son is doing more than most to bring that day closer. He seems to feel a responsibility to spur human development, too — a responsibility to ensure people “work harder” to avoid a future in which computers “totally overwhelm us.”

Noting that an individual genius might have an IQ of only 200, he poses the question, “What can such people achieve if they work together?”

Son hopes to find out by funding the members, who he calls “representatives of humans.” With a net worth estimated at around $22 billion, it’s a gamble the onetime aspiring schoolteacher can afford to take.